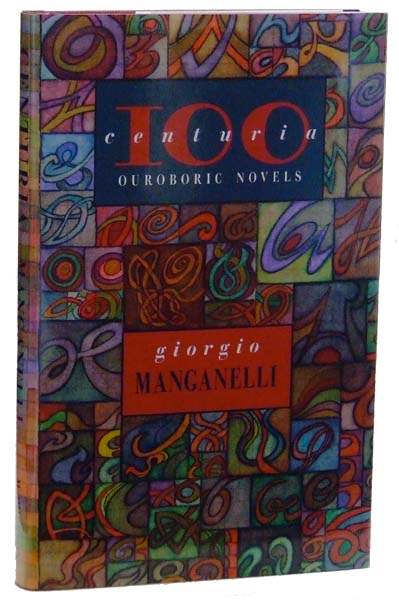

Centuria : One Hundred Ouroboric Novels (cloth)

SKU:

1720

$24.00

$24.00

Unavailable

per item

Clothbound, sewn, jacketed, 224 pages, 5.5 x 8.5", 2005, 0-929701-72-0

For the paperback, go here.

Translated from the Italian by Henry Martin

Winner 2005 ForeWord Book-of-the-Year 2005 Silver Medallion for Translation

Jhumpa Lahiri in the New York Times Book Review on Sept. 8, 2013: "I recently discovered the work of Giorgio Manganelli, who wrote a collection called 'Centuria,' which contains 100 stories, each of them about a page long. They’re somewhat surreal and extremely dense, at once fierce and purifying, the equivalent of a shot of grappa. I find it helpful to read one before sitting down to write."

Italo Calvino once remarked that in Giorgio Manganelli, "Italian literature has a writer who resembles no one else, unmistakable in each of his phrases, an inventor who is irresistible and inexhaustible in his games with language and ideas." Nowhere is this more true than in this Decameron of fictions, each composed on a single folio sheet of typing paper. Yet, what are they? Miniature psychodramas, prose poems, tall tales, sudden illuminations, malevolent sophistries, fabliaux, paranoiac excursions, existential oxymorons, or wondrous, baleful absurdities? Always provocative, insolent, sinister, and quite often funny, these 100 comic novels are populated by decidedly ordinary lovers, martyrs, killers, thieves, maniacs, emperors, bandits, sleepers, architects, hunters, prisoners, writers, hallucinations, ghosts, spheres, dragons, Doppelgängers, knights, fairies, angels, animal incarnations, and Dreamstuff. Each "novel" construes itself into a kind of Möbius strip, in which, as one critic has noted, "time turns in a circle and bites its tail" like the Ouroborous. In any event, Centuria provides 100 uncategorizable reasons to experience and celebrate an immeasurably wonderful writer.

To download a sample of Centuria, click the link below.

For the paperback, go here.

Translated from the Italian by Henry Martin

Winner 2005 ForeWord Book-of-the-Year 2005 Silver Medallion for Translation

Jhumpa Lahiri in the New York Times Book Review on Sept. 8, 2013: "I recently discovered the work of Giorgio Manganelli, who wrote a collection called 'Centuria,' which contains 100 stories, each of them about a page long. They’re somewhat surreal and extremely dense, at once fierce and purifying, the equivalent of a shot of grappa. I find it helpful to read one before sitting down to write."

Italo Calvino once remarked that in Giorgio Manganelli, "Italian literature has a writer who resembles no one else, unmistakable in each of his phrases, an inventor who is irresistible and inexhaustible in his games with language and ideas." Nowhere is this more true than in this Decameron of fictions, each composed on a single folio sheet of typing paper. Yet, what are they? Miniature psychodramas, prose poems, tall tales, sudden illuminations, malevolent sophistries, fabliaux, paranoiac excursions, existential oxymorons, or wondrous, baleful absurdities? Always provocative, insolent, sinister, and quite often funny, these 100 comic novels are populated by decidedly ordinary lovers, martyrs, killers, thieves, maniacs, emperors, bandits, sleepers, architects, hunters, prisoners, writers, hallucinations, ghosts, spheres, dragons, Doppelgängers, knights, fairies, angels, animal incarnations, and Dreamstuff. Each "novel" construes itself into a kind of Möbius strip, in which, as one critic has noted, "time turns in a circle and bites its tail" like the Ouroborous. In any event, Centuria provides 100 uncategorizable reasons to experience and celebrate an immeasurably wonderful writer.

To download a sample of Centuria, click the link below.

Also available from:

-

Reviews

-

Sample text

<

>

THE REVIEW OF CONTEMPORARY FICTION

A friend once pointed out the fallacy of describing narratives as circular. A narrative can contain elements that are recurrent, but a truly circular narrative would be endlessly repetitive, with no beginning or end, pages around a central core like a novelistic Rolodex. (Joyce apparently envisioned something similar for Finnegans Wake.) This is worth keeping in mind while reading Centuria, whose subtitle, of course, promises 100 “ouroboric” novels (which average a page and a half and which could also be classified as short-shorts, exempla, fabliaux, or “novels from which all the air has been removed”). In precise and sometimes stiff prose (e.g., “the gentlemen’s deaths . . . confute this putative salubrity of the air”) most of the early novels describe “a gentleman” in dramatic if ordinary circumstances of love and indifference, of doubt and mistrust, of experiencing the relief that comes with romantic rejection. But soon, en masse, these gentlemen start dying at train stations, spontaneously crumbling to dust, and carrying their heads like saints. Then ghosts start to take center stage, and dragons, living spheres, and dinosaurs. Many of these figures recur in the other “novels,” but don’t strictly repeat, which brings us back to the ouroboros, the tail-biting snake of Centuria’s subtitle. The eternally circular ouroboros is generally accepted to symbolize life’s completion and renewal, but bear in mind that the ouroboros is actually a snake that’s eating itself in a nihilistic, autophagous felo-de-se, and it seems that Manganelli might have envisioned Centuria not as circular (which it’s not—its recurrent elements are more symphonic, like Curtis White’s Requiem or even Calvino’s Invisible Cities), but as ouroborically destructive. But it’s a particular kind of destruction: as fire is cleansing, Centuria is metadestructive, immolating itself (and, by extension, its traditions), but leaving in its place something new and pure and often spellbinding. [Tim Feeney]

A friend once pointed out the fallacy of describing narratives as circular. A narrative can contain elements that are recurrent, but a truly circular narrative would be endlessly repetitive, with no beginning or end, pages around a central core like a novelistic Rolodex. (Joyce apparently envisioned something similar for Finnegans Wake.) This is worth keeping in mind while reading Centuria, whose subtitle, of course, promises 100 “ouroboric” novels (which average a page and a half and which could also be classified as short-shorts, exempla, fabliaux, or “novels from which all the air has been removed”). In precise and sometimes stiff prose (e.g., “the gentlemen’s deaths . . . confute this putative salubrity of the air”) most of the early novels describe “a gentleman” in dramatic if ordinary circumstances of love and indifference, of doubt and mistrust, of experiencing the relief that comes with romantic rejection. But soon, en masse, these gentlemen start dying at train stations, spontaneously crumbling to dust, and carrying their heads like saints. Then ghosts start to take center stage, and dragons, living spheres, and dinosaurs. Many of these figures recur in the other “novels,” but don’t strictly repeat, which brings us back to the ouroboros, the tail-biting snake of Centuria’s subtitle. The eternally circular ouroboros is generally accepted to symbolize life’s completion and renewal, but bear in mind that the ouroboros is actually a snake that’s eating itself in a nihilistic, autophagous felo-de-se, and it seems that Manganelli might have envisioned Centuria not as circular (which it’s not—its recurrent elements are more symphonic, like Curtis White’s Requiem or even Calvino’s Invisible Cities), but as ouroborically destructive. But it’s a particular kind of destruction: as fire is cleansing, Centuria is metadestructive, immolating itself (and, by extension, its traditions), but leaving in its place something new and pure and often spellbinding. [Tim Feeney]

To download a text sample, click here.centuria_ch17-19.pdf